This post originally appeared on the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s Riverwise website on June 25, 2020

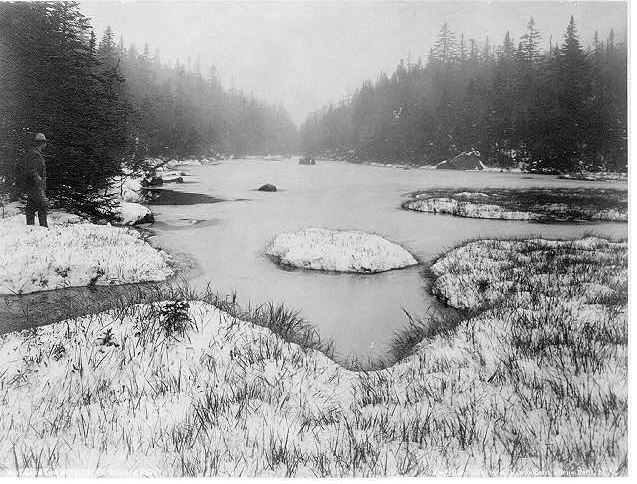

The Hudson, the River that flows both ways has been a transportation corridor for hundreds of years before Europeans first saw it. The Hudson rises in the mountains at Lake Tear of the Clouds in Essex County, NY and empties into Upper New York Bay. The Hudson is a drowned river as its bottom is below sea level almost all the way to Albany. The Hudson is also considered a fjord one of very few in North America. The River has been a commerce highway for as long as humans have inhabited the North American continent. Henry Hudson and other early European explorers were convinced that the River was part of the Northwest Passage.

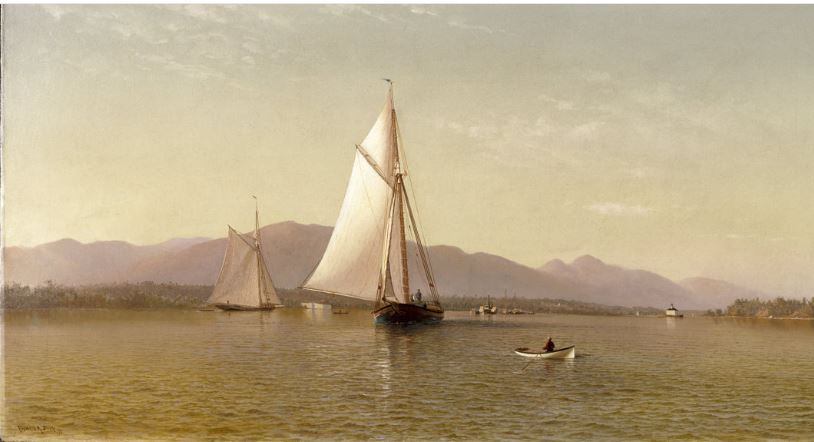

The Hudson River once formed a bustling highway linking even the smallest communities to a web of regularly scheduled commercial routes. Schooners, sloops, barges, and steamboats provided a unique way of life for early river town inhabitants. Farmers, merchants, and oystermen relied on this vibrant and diverse fleet of vessels to bring in supplies and deliver their goods to market. This arm-of-the-sea was an integral part of the lives of those who worked New York’s inland waters.

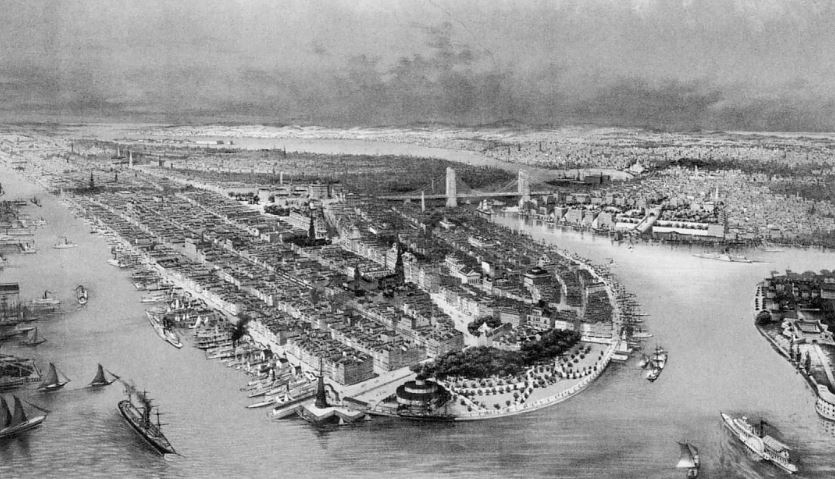

The Hudson is connected through New York Harbor to the Coast and the rest of the world. With one of the world’s greatest ice-free harbors on earth, New York City was built on a shipping industry that has over time become a dangerously tenuous lifeline to the outside world for the region. Today the far-flung international trade network that once pumped vibrant economic life into the region threatens to collapse as imported natural resources and the fossil fuels needed to transport them become increasingly scarce and expensive. Higher petroleum costs, and higher wages in countries in which much of our imported goods are made could snap that lifeline.

New York State’s working waterfronts have long been a key contributor to the region’s financial well-being and our nation’s economy. But, in a carbon constrained future, how will goods and people be moved from place to place, and what role will the Hudson River play in this vision?

How should we meet the looming challenges of climate change, rising sea level, aging infrastructure, changes to global shipping patterns, threats to food security, and the risks these changes bring to New York’s Hudson Valley.

The biggest question of all: How do we address this daunting multitude of challenges and turn them into opportunities for transforming waterfronts and ports to effectively and efficiently serve our regional economy far into the future?

The solution in this time of rapid change may be a return to the “Slow Technology” of our recent past — sail powered freight ships – and to the present, solar powered ferries and barges. Tomorrow, New York City’s port and the ports of the Hudson Valley will likely continue to be a commercial hubs due to their strategic location, but those harbors will likely resemble their 18th and 19th century selves rather than the ports we know today.

We hope the “RiverWise: North Hudson Voyage” has served to engage the public and commercial interests along the Hudson in how these two important examples of 19th and 21st Century technology will create opportunities for communities to re-examine how their waterfronts will be used for recreation, conservation, and commerce. This voyage of discovery is the first of many with more and more ships joining this flotilla of hope and inspiration.

The next step will be even more critical, to commit to honestly confronting challenges, while also boldly embracing opportunities and possibilities. We must move forward quickly and vigorously, and we need to do more. We must inspire individuals, communities, local leaders, city and state governments to commit to creating a thriving, post carbon transportation and logistics system. We must also commit to the creation of a network of sustainable blue waterways in a region that advocates for a post carbon transition that people will embrace as a collective adventure, as a common journey, as something positive, and above all, as a future full of Hope.

Leave a Reply