A Blog Post by Steven Woods. Mr. Woods earned his master’s degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College in 2021, with an undergraduate degree in History from LeMoyne College. He has worked in museums for over 20 years and is making a career transition to the sustainability field after 6 years in the US Airforce. He is presently the Solaris Coordinator at the Hudson River Maritime Museum.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A shorter, slightly less technical version of this blog was originally posted by the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s History Blog. As theMuseum and The Center for Post Carbon Logistcs have different missions, the publication of two different versions was deemed appropriate.

I’m willing to bet a lot of people clicked this article thinking something along the lines of “How about ‘Towards Hiring A Proofreader, Eh?!’” Despite this, the title is accurate: The Food Movement lacks any real vision of how food will move in future from the farm gate to the citizen’s fridge. I am very much talking about a social movement concerned with the physical movement of food.

We could also call such a movement by other names: “Tucker Transit To-Do,” “Respect For Refreshment Relocation,” “Comestible Conduct Concern,” “Victual Voyage Verification,” and “The Food Flow Front” were all suggested to friends before I was summarily kicked out of their house. While “Whence The Vittles?!” was a personal favorite, it seems these are mostly just good ways to make enemies and alienate people while not getting your point across in a helpful way. Thus, we are left with the boring but utilitarian name of The Food Movement Movement.

There are a lot of studies out there about regional food self sufficiency, some dating from the 19th century, and others from just a few years ago. The topic of food sovereignty has been a matter of debate since the 17th century, and usually comes to the fore during and after armed conflicts and other crises which might result in embargos or other interruptions to the food supply, such as Brexit quite recently. Agriculture and food security have long been considered matters of national security and tools of foreign policy, and in war many blockades specifically target food movement into and within enemy nations as a way of inflicting losses and destroying the enemy’s will to continue the conflict..

Far fewer studies actually touch upon how food is supposed to move between its points of origin and consumption within a peacetime food system model. Even fewer touch upon how this can be done at the necessary scale in a post-carbon future.

How food was, is, or will need to be carried over land and sea through the use of self-propelled vehicles, trailers, barges, carts, pack animals, ships, or human powered systems such as bicycles is chronically under studied. A great historical study of this overlooked element of food systems is Walter Hedden’s book “How great cities are fed” from 1929. Without this transportation, food goes to waste and people starve. It is simply impossible for New Englanders to eat food which is sitting in crates on a Texas, Florida, Kansas, or California farm table for lack of transportation capacity. As a result, it is difficult to overcomplicate or underestimate the impact of insufficient transport capabilities on any socio-alimentary system.

With a carbon-constrained future rapidly approaching and demanding significant changes to transportation habits, this issue is of paramount importance. Unfortunately, it is routinely ignored in food system visions, which are normally published without direct and detailed attention to the distance and means by which food will be transported. Take New England, for example: A New England Food Vision by Food Solutions New England hopes to expand agriculture so half of New England’s food is produced within the region by 2060. While laudable and achievable, this publication doesn’t tell us how literally tens of thousands of tons of food per day will arrive in New England from elsewhere, all year round. The study simply assumes there are sufficient transport resources which are independent of petroleum fuel supplies, will not raise the cost of imported food beyond the reach of citizens, and doesn’t rely on similarly vulnerable, scarce, and unpredictable renewable electricity sources. It also expects petroleum-based paved infrastructure, tires, and other supplies underpinning our current transportation system to continue existing in sufficiently decent condition to carry these millions of daily ton-miles across the region and the continent.

None of this should be taken for granted, but it is easy to understand why it is forgotten in our current economy and era of easy access to energy. With cheap fossil fuels, low shipping costs, and a probably misplaced faith in miracle technologies, we as a culture and a nation have a tendency to get carried away with the thought of our current transport system existing forever. It is honestly difficult to imagine anything else, even when you put your mind to it.

So, the need clearly exists for a Food Movement Movement. But how would it operate? What vehicle could possibly provide New England’s massive import requirements with oil- and electricity-independent, renewable, reliable, and emissions-free transportation without the need for paved infrastructure? The answer isn’t terribly difficult to find for those who have studied the region’s history: Sailing Vessels.

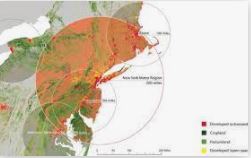

Visit any one of the dozens of Maritime Museums in New England, and you can see there is plenty of tradition, knowledge, and capacity to supply New England’s food imports by sail freight. By my calculations (Pages 74-78 Here), a mere 3,000 ships and 18,000 sailors would be able to meet this demand with room to spare for a small amount of delays, time off, and some commodities I hadn’t included in the original math. This is with small vessels, too: A ship of only 111.5 tons cargo capacity, with a crew of 6.5 sailors was used as the rule.

It is eminently possible to build, launch, and crew these vessels over the next 40 years, while creating tens of thousands of jobs. It is also more than possible to use existing training infrastructure from organizations such as Tall Ships America, US Sailing, and The American Sailing Association to ensure a sufficient pool of skilled windjammer sailors are at hand to take them over the seas.

This fleet only supplies the import needs of New England. The Coastal Trade in New England is prime territory for exploitation by enterprising Yankee Sailors, due to the historical settlement patterns of the region. Dozens of small ports and harbors can become points of carbon free shipping within the region, as was seen with the Vermont Sail Freight Project and Maine Sail Freight. These projects have shown the way to a Slow Food Movement Movement, though some brokerages and other infrastructure will need to be built to support this type of transportation. This type of business pattern change is a minor thing in all reality, and can be accomplished if we set some Yankee determination and ingenuity to work on it.

Far larger areas than just New England can be served by Sail Freight: Cities and towns along all four of the USA’s coastlines (Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf of Mexico, and Great Lakes) can benefit from Sail Freight, as can the massive regions of the midwest served by our over 12,000 miles of inland waterways. As with any other such infrastructure, ports, harbors, anchorages, channels, locks, dams, sluces, dry docks, weirs, inclined planes, and shipyards must be maintained every year, fully funded, and cared for. However, unlike other infrastructure investments, they are long term, lasting up to or in excess of 50 years for locks, and support carbon free shipping in the place of resource-intensive gas, diesel, and electric powered vehicles.

As we think of Slow Food, we should keep in mind the importance of moving that food around the block and around the world as sustainably as it was grown. With a bit of planning, civic involvement, prudence, and forethought, far more than just the slow food movement can benefit from the slow movement of food.

Leave a Reply