Summary:

Harvest the Past to Power the Future

Wellbeing Farm will explore an array of innovative heritage and leading-edge technologies by which individuals, communities, and the Hudson Valley Bioregion can thrive in decades ahead – designing and realizing pragmatic, environmentally and economically sound tools for peacefully, equitably, and intelligently transitioning away from fossil fuels.

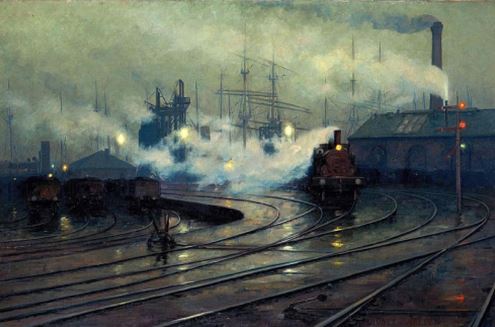

Imagine a place here in the Hudson Valley where skilled craftspeople, technicians and visionaries travel back in time to harvest the best, most energy efficient and practical technologies of bygone eras, then retool and repurpose those technologies to meet the challenges of our Post Carbon Future.

Wellbeing Farm is that place, and the time for its genesis — here among our forested hills and in our fertile river valley — is now.

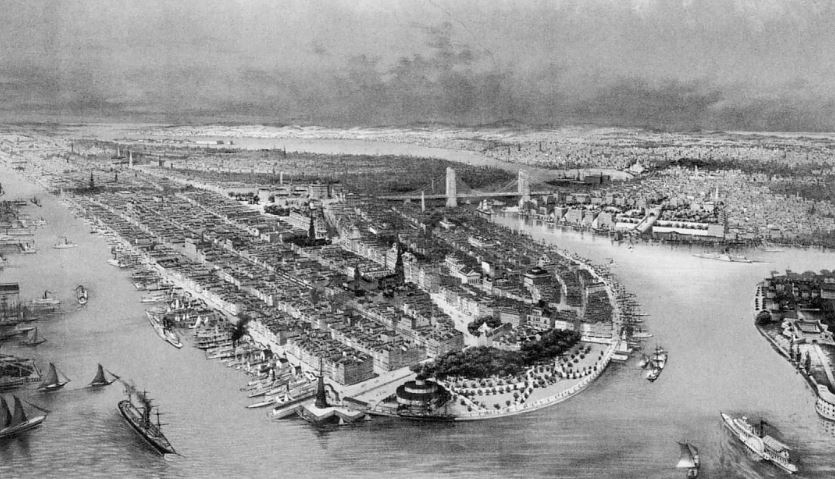

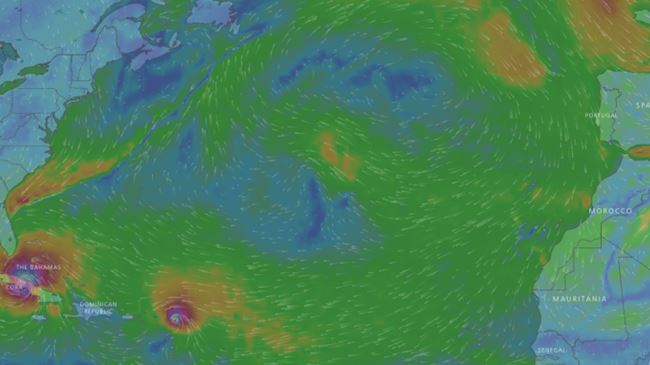

Located in the heart of the Hudson Valley Bioregion, Wellbeing Farm will be a working farm with access to a river port, that will engender the Valley’s can-do spirit, harness our region’s inventiveness and our love of innovation, allowing our region and its people to not merely survive in the Post Carbon era, but thrive. And why not? After all, our region gave the world the steamboat, the telegraph, the submarine, FM radio, the first interactive software systems vital to today’s computers, and even potato chips. We seem born to invent the future!

Wellbeing Farm will be located on one large site or multiple locations in the Mid-Hudson Valley — a real place, or a scattering of several organizationally linked places — that will address the entwined themes of education, food production, alternative energy production, health and wellness, and the equitable distribution of knowledge, facilitating the transfer of an abundance of innovative traditional processes, technologies, and products to the local community.

Wellbeing will be an “invention factory” of an entirely new and surprising sort. The source of its inspiration and empowerment will be our region’s earth and waters, its hands, and minds. Here the best and brightest urban and rural, “Slow” technologists, craftspeople, educators, artists, schoolchildren, seniors, can come together to remake our post-modern world. Here they’ll find new, efficient, green ways to produce energy; revolutionize agriculture to assure food security in an increasingly unstable world; reinvent transportation on land and water to move goods up and down our valley and beyond. Here they’ll help birth a new inclusive regional economy that rewards all citizens, while celebrating democracy, cooperation, and public service.

On the farm, every day, diverse participants — Transition and Permaculture practitioners, farmers, wranglers, post and beam builders and boat builders, commercial fishermen, millwrights, engineers, potters, weavers, woodworkers, writers, historians, archivists, computer and IT experts, and people from wildly diverse vocations — will merge and meld their talents.

Here, they’ll move via hands-on experiences beyond spin and abstract buzzwords – past “environmental”, or “sustainable”, or “eco” this or that. Here, our work will focus on a Just Transition away from fossil fuels, giving new meaning to the word farmhand, as all join together to create the naturally viable means for living and being in community in the 21st Century — as we prosper economically, emotionally, and spiritually, beyond the realm of coal and oil.

Wellbeing Farm will be a center for Permaculture, the crafts of Transition, and for re-skilling. It will be a showplace, offering living demonstrations of the efficacy of local food and energy production, a place where practitioners will be given the time and space to develop and implement solutions intended to move the world away from an extraction and unlimited growth paradigm; toward a sustainable, steady-state economy that benefits the local community, its small businesses and residents.

Most of all, Wellbeing Farm will be a place to dream, and realize those dreams, a place to be nurtured by our heritage, to experiment and boldly face the challenges of a post-pandemic, post carbon, human community — a place to grow crops, breed livestock, construct new buildings and boats, and an empowered future for the Hudson Valley Bioregion.

WELLBEING FARM

A place to explore Transition, Re-skilling, Permaculture, and Slow Tech, while meeting the challenges of our Post-Carbon Future.

Wellbeing is defined as a “happy, healthy, or prosperous state.” Wellbeing Farm, therefore, will be a physical place where the principles of wellbeing in a post-carbon age are practiced, where Permaculture (an approach to designing human settlements and agricultural systems reflecting and conserving the natural world), and Transition (where those same principles, as well as other innovative approaches), are applied to solving the dual challenges of climate change and peak oil within the Hudson Valley Bioregion.

The necessity for establishing Wellbeing Farm first occurred to me and others in 2013 at the Mid-Atlantic Transition Hub Waterways Reskilling Gathering, when it became clear that those who attended and presented – Transition and Permaculture practitioners, farmers, millwrights, boat builders, post and beam barn and mill restorers, commercial fishermen, engineers, potters, weavers, and woodworkers — all needed a physical location and community center, a place to be, gather, hold workshops, teach classes, congregate, train apprentices, share stories, and create real world solutions to achieve an urgent Transition into the post-carbon Appropriate/Slow Tech era.. Slow Tech urges a thoughtful, empowering, nature-based process, utilizing a variety of scaled down tools with which to reshape human relationships, conserving time, energy, and our bioregional home.

Well Being Farm will address the entwined themes of education, food production and alternative energy production, health and wellness, and the equitable distribution of knowledge, along with the transfer of an abundance of innovative traditional processes and products to the local community.

Wellbeing Farm will be a physical place, located in the heart of the Hudson Valley Bioregion, where participants can move, by means of, hands-on experiences beyond abstract buzzwords – past “environmental,” or “sustainable, or “eco” this or that. Here, their work will focus on a Just Transition, giving everyone the tools needed to create the naturally viable means for living and being in community every day, on into a positive future — as we prosper economically, emotionally, and spiritually, beyond the realm of coal and oil.

Wellbeing Farm won’t only teach pragmatics skills and livelihoods; it will be a living laboratory in which participants take part in designing Transition – where teachers and learners join in a collective adventure and commit to a common journey, originating pathways that lead beyond fossil fuels, helping people feel not like cogs in a faceless corporate gear, but like active, vital, creative individuals involved in the important work of revolutionary societal transformation.

Wellbeing Farm will be a center for Permaculture, the crafts of Transition, and for re-skilling to meet the challenges of a post-carbon world. The Farm will be a showplace, offering living demonstrations of the efficacy of local food and energy production, a place where practitioners will be given the time and space to develop and implement solutions intended to move the world away from an extraction and unlimited growth paradigm; toward a sustainable, steady-state economy that benefits the local community, its small businesses and residents.

Wellbeing Farm; the basics:

- The Farm will be centrally located in the Hudson River Bioregion.

- It will be a Transition Community based on Permaculture principles.

- It will be a “Folk School” modeled after, and incorporating the best aspects of, the Whatcom Folk School, Ralph Borsodi’s School of Living, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, Pfeiffer Center, Snow Farm, Peters Valley Craft Center, North House Folk School, Kinstone Academy of Applied Permaculture, Adirondack Folk School, Hudson River Maritime Museum’s Wooden Boat School, Yestermorrow School, and Penland School of Crafts.

- Wellbeing Farm will house the headquarters of The Center for Post Carbon Logistics, the Hudson Valley Resilience Hub, and the Bioregional Traditional Knowledge Database and Library – offering these institutions one central place where colleagues can share expertise, experiences, stories, electronic and physical resources. Wellbeing Farm will serve as a “living library,” gathering and protecting historical knowledge, while exploring and promoting innovative sustainable solutions based in traditional crafts and skills.

- The farm will regularly host the annual Hudson Valley Common Ground Country Fair, Chautauquas, and other bioregional celebrations.

Wellbeing Farm Mission

Wellbeing Farm will explore an array of innovative heritage and leading-edge technologies by which individuals, communities, and the Hudson Valley Bioregion can thrive in decades ahead – designing and realizing pragmatic, environmentally and economically sound tools for peacefully, equitably, and intelligently transitioning away from fossil fuels.

Wellbeing Farm will serve as an empowering example – demonstrating ethical livelihoods and teaching beneficial technologies that do minimal socio-environmental harm; methodologies that foster self-reliance and promote Slow Tech via hands-on practices, as professionals and students gather regularly from across our bioregion on a farmstead like no other in our region: a living laboratory cultivating not only resilient food production methods and energy and transportation solutions, but fresh, pathfinding ideas as well.

The Farm will take its essential lessons from nature, incorporating the values of earth stewardship, community cooperation, and individual initiative, while emphasizing the sharing of surplus, teaching that our actions have consequences, that we all have vital responsibilities, and ultimately fostering care and love for the environment, society and for each other.

The Power of Just Doing Stuff

Wellbeing Farm will teach traditional skills and re-skilling for a post-carbon world. It will house Permaculture demonstration projects; alternative energy and water conservation pilot projects; and a plethora of innovative educational activities offered up within beautiful, peaceful, productive, energy-efficient spaces where students, scholars and practitioners can meet, perhaps live, and learn from each other.

The farm will not stand alone, but will be integrated into the greater Hudson Valley community, with which it will engage collectively and creativity to unleash an extraordinary, historic Transition to a future beyond fossil fuels; a future that is vibrant, abundant, resilient, and ultimately preferable, more equitable, and more economically viable than the current model:

- Wellbeing Farm will be a physical place, showcasing the efficacy of producing local food and power in our bioregion.

- It will provide the space, time, structure, and opportunities needed in which practitioners can develop implementable ideas for achieving a locally focused, highly functioning, steady state economy.

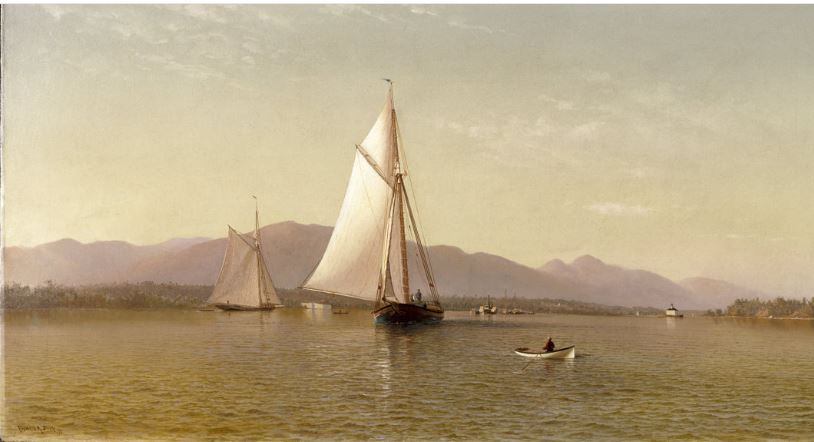

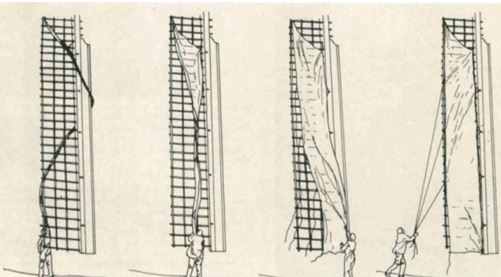

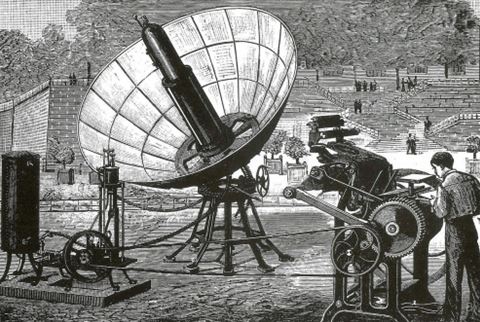

- The Farm’s workshops will preserve the skills and tools of the past, reworked and transformed into crafts that will serve us adroitly in a carbon constrained future. Among those skills: Wood fired ceramics; small scale iron forging and bronze casting; traditional rope making (using locally harvested natural fiber); woodworking; stone and thatch work; “passive – zero net energy” building design and construction; wind, water mill, and solar steam energy solutions; leather working to create tack for working horses; beer, cider, and spirit distilling utilized in food preservation and medicine making; “bio-digestors for methane and fertilizer; low carbon transportation (including “short sea” sailing freight vessels appropriate to the Hudson River, Hudson Estuary and coastal trade), plus a multitude of other post-carbon commerce and communication technologies.

- Wellbeing Farm will provide educational opportunities for experimenting with, and realizing, real world solutions to the environmental, economic, and social crises we face today, and those we will face on into the future.

- Wellbeing Farm will enable people working locally to transition our Hudson Valley communities and the bioregion from a consumptive industrial model to a restorative model — shifting to a truly sustainable economy dedicated to core values of human and environmental health, cultural and biological diversity, care for commonly held resources, and cooperative nonviolence.

- Wellbeing Farm will, above all, focus on Transition: on the common journey we must all take together if civilization is to thrive, evolve and fulfill our dreams for a better world. This will not be a journey born of desperation or despair, but one that is joyful and empowering. To paraphrase the title of Rob Hopkins’ book: Wellbeing Farm will embody the Power of Just Doing Stuff!

Wellbeing Farm; Three Organizing Principles

Principle 1: Permaculture — Permaculture practitionersdesign ecologically-sound human habitats and food production systems. This discipline strives for the harmonious integration of human dwellings, farming techniques, and communities within the surrounding natural world, including the microclimate, annual and perennial plants, animals, soils, and water. The focus is not on these individual elements, but rather on the shifting relationships between them to create a prosperous balance between human and natural communities. This synergy is enhanced when human systems actively mimic patterns found in nature.

The core tenets of Permaculture are:

• Take Care of the Earth: Provide first for all life systems so they flourish and multiply.

• Take Care of the People: Offer everyone access to the resources needed to thrive.

• Share the Surplus: Healthy natural/human systems generate plentiful outputs for all.

Permaculture principles practiced at Wellbeing Farm will entail eco-friendly food production, and far more. Energy-efficient buildings, nature based wastewater treatment, recycling, and land stewardship are other key holistic components.

Permaculture on the Farm will include research into practical economic and social structures that support the evolution and realization of more sustainable communities, encompassing co-housing and eco-village models, for example. Participants at the Farm will look closely at ways in which we can all interact productively, while respecting and working closely with nature.

Principle 2: Transition — The Transition Movement represents one of the most promising models available to modern society today for engaging individuals and communities in the far-reaching actions required to mitigate the negative socio-economic-environmental impacts of peak oil, climate change, and the global financial crisis. A key component of Transition is a move away from a large-scale, global production/distribution model and toward re-localization – achieving fulfilling and equitable local livelihoods, lived in harmony with home bioregions.

Underpinning Transition is an understanding that peak oil, climate change and the global economic crisis require urgent local action now. Without that immediate action, an era of far-more-costly fossil fuels – marked by disastrous global supply chain interruptions and shortages – looms and is inevitable.

Industrial society has lost the resilience needed to cope with such system shocks. So immediate adaptation is essential. And we must act together, using all our skill, ingenuity and intelligence, our home-grown creativity and cooperation, to unleash the collective genius of local communities and our bioregion to achieve an abundant, connected, and healthier future for all.

Wellbeing Farm will not need to reinvent the wheel to meet these Transition challenges.

Transition US is an already existing, and vital resource for building resilient communities in the United States, while Kingston New York Transition is tuned into local issues and solutions. Both organizations are linked into the worldwide Transition movement in which hundreds of interconnected communities foster their own unique local initiatives, benefiting all.

In addition, The Good Work Institute envisions a Just Transition to environmentally sustainable and resilient systems in the Hudson River Bioregion by advancing ecological restoration; democratizing communities, wealth and the workplace; fostering racial justice and social equity; re-localizing production and consumption, and retaining and restoring cultures and traditions.

Principle 3: The Folk School – Wellbeing Farm will operate utilizing five well-established Folk School philosophies and values: 1). Re-skilling – offering training in a varied range of past and contemporary practical tools and skills; 2) Inclusivity – assuming everyone has something to add to the journey, and to creating a more sustainable and resilient Hudson Valley; 3) Honoring Elders – recognizing that the young can learn invaluable lessons from elders with unique skills and stories to share; 4) Awareness – Transition requires we give up old paradigms to create a viable, abundant future; 5) Networking – cooperation, not competition, is the key to all citizens benefiting from innovative new learning opportunities.

Wellbeing Farm; Creating a Sense of Place

The physical location, acreage, scope of programs and services at Wellbeing Farm will be dependent on funding and upon the needs of practitioners in the Hudson Valley Bioregion. It may begin small, then grow to meet our post-carbon societal and educational needs.

As we envision it today, Wellbeing Farm will be centrally located on multiple acres in the Mid-Hudson Valley. It could be centered at a single location, or scattered at several, depending on availability of facilities, land, and community need. It should be located near public transportation, near or on a major body of water, and sited near other sustainable activity centers and established institutions such as the Farm Hub, Esopus Agriculture Center, Arrowhead Farm Agricultural Center, Garrison Institute, and the Omega Institute.

Element 1: The farm itself – No matter where situated, Wellbeing Farm must offer a welcoming, bucolic, stimulating, beautiful landscape in which to think, work, create and write – a place where practitioners can experience relationships between human beings and the natural world. Instructors and mentors will be drawn from a wide variety of disciplines and experiences; they will require physical amenities to achieve their teaching goals, for example:

- Builders will require sufficient land to construct full-sized buildings, for teaching post and beam, cob, cordwood, stone and thatch construction, and other green building methods.

- Millwrights will need a place to build/repair water and wind projects

- Farmers, foresters, and those working with horses will need sufficient land and facilities for crops and livestock, to practice veterinary skills, harness making and repair, and for modifying tractor-drawn machinery for horses.

- Sail freighters will require a dry dock and waterway on which to build / rebuild small sail freight boats, learn rigging, and seamanship.

- Wild foragers will require forest, meadow, and wetland habitat in which to teach forest gardening and gleaning techniques. Boyers (bow makers) and gunsmiths will likewise need a place where natural materials and tools are available.

- Furniture makers must have a local source of wood, a sawmill, drying shed, and workshops.

- Weavers will need a wool source, plus a place to clean, spin, and dye.

- Potters will require clay, wheels, kilns and shelter.

- All participants will need a place to socialize and learn skills from each other.

- Ultimately, what may evolve is a centralized Wellbeing Farm facility, surrounded by nearby satellite locations providing all sorts of teaching opportunities for people of all ages.

- Also, a portion of the farm must be left undisturbed and natural, serving as a place for nature observation and solitary contemplation.

Element 2: The Bioregional Traditional Knowledge Database – Wellbeing Farm will serve as a repository for vital traditional knowledge — encompassing arts, crafts, livelihoods, and connections to our natural heritage, all in danger of disappearance. This database will form an “extraordinary source of knowledge and cultural diversity from which the appropriate innovation solutions can be derived today and in the future.”

The Farm’s bioregional database will emulate and interface with the UNESCO International Traditional Knowledge Institute (ITKI) an ambitious project intended to preserve, restore, and promote the re-use of traditional skills and inventions from all over the world. ITKI includes among its important resources an online encyclopedia of low-tech know-how.

The physical and electronic database at Wellbeing Farm will include a collection of books, blueprints, photos, and drawings showing how things were made and how we fed ourselves in a pre-carbon world – including resources such as the Whole Earth Catalog, books published by Shelter Publications, the Foxfire books, mechanical engineering texts, trade encyclopedias, and downloaded and printed reproductions like Small Hydropower Systems, home built windpower, and books and resources for pre-petroleum technology.

Element 3: Common Ground Fair Hudson Valley – Working with the New York Organic Farming Association (NOFA-NY), Wellbeing Farm will provide space for an annual “Common Ground” Country Fair. This event will bring together a large gathering of farmers, change agents, artisans, musicians, Slow Money social entrepreneurs, Permaculture and Transition practitioners, Eco-Villagers, organic farmers, fishermen, seed companies, natural food stores, chefs, cooperatively owned small businesses and thousands of families from throughout the region interested in manifesting and welcoming a new approach to the future. This event, along with other celebratory activities will generate strong lasting bonds between the Farm and surrounding communities.

Element 4: Educational Opportunities for Children – Wellbeing Farm is, above all else, a place where people of all ages can learn. And while many participants will be adults honing new skills, it is vital that an honored seat at the table be maintained for children, and for their education.

Permaculture as a design system is rooted in an understanding of ecological principles – and it is best if that understanding is cultivated early, through sensory awareness of the natural world, natural cycles, energy flow and interconnectedness. For that reason, the farm will foster a close relationship with Hudson Valley Bioregion schools pre, primary and high schools, and existing programs such as Creek Iverson’s Seed Song Farm Summer Camp, and Wild Earth’s summer camp. Field trips will often arrive at the Farm, bringing young people to see how their world is being re-skilled; likewise, practitioners will travel to schools often to teach a range of new livelihoods.

In this way, the Farm will help ensure that our children have the best possible start to understanding the “why” behind the “how” of our Permaculture ways — learning skills that far transcend the deskbound limitations of old school education models. Children will be introduced to a vast range of hands-on crafts and folk art skills, ranging from toolmaking to basketry; clothing construction, fiber and fleece production; gardening and farming, gleaning and food preparation; learning to work with and respect working animals; while also cultivating a love for traditional, self-made music, storytelling, nature observation, and much more.

Wellbeing Farm; Why Now?

We live at a highly precarious – but also fascinating and hopeful – point in history. The convergence of massive challenges, particularly climate change, peak oil, and the global economic crisis, has brought us to an historical moment where we are profoundly prompted to act.

We the People are surrounded by “experts” telling us that we have gone too far, that civilization, and maybe humanity, are doomed; and worse that our end is inevitable – that the web of life as we know it will collapse catastrophically and soon.

While these dangers are real and dare not be dismissed, at the same time something very powerful and positive is stirring, taking root the world over and in our own bioregion. People are choosing life and manifesting that empowering choice in their daily lives and communities.

The magnitude of the challenge ahead is huge, and the obstacles are plenty. But there is an emerging energy, positive spirit, and the will to succeed and thrive. There is a sense of exhilaration arising out of our talking and listening to each other, to not accepting the faltering status quo, but envisioning what we want and then rolling up our sleeves and starting to co-create it.

There is no denying the challenges we face, but there is also no denying the practical, instinctual, democratic response that is arising among We the People today. In towns and cities everywhere we are asking each other: “What can I do right now? How do we get started?”

In a world of rapidly diminishing resources and increasing stresses on natural and social systems, we must rapidly join to implement innovative equitable strategies to restore degraded landscapes, to feed all people well, to convert our energy-wasteful infrastructure into holistic natural/human systems that benefit everyone. Wellbeing Farm is part of that vision – a real place in the Hudson Valley Bioregion where we can create a bountiful future together.